I’ll start this post with a sad but necessary admission: several months ago, I quietly gave up and stopped trying to prevent death and suffering through Jewish communities.

The truth is that leading this initiative has been a rewarding but very frustrating experience for me. I’ve tried to remain positive throughout, but hundreds of one-on-one meetings around the project left me—despite everyone who stepped up and the many, many people we managed to help together—with a sense of disappointment and personal burnout.

A few months ago, I realized that I needed to take a break from this work—which I’ve been doing voluntarily without pay for a while—if I want to continue doing good in the world with a mind and heart free of bitterness and frustration.

Since I started this initiative, I’ve had the sense that a lot is at stake, and finding myself taking a big step back was hard.

After taking some time off to think, I still believe this initiative can do a lot more good, but this starts with an honest examination of where it’s at (and where I’m at).

Before I continue, it’s important for me to stress that I remain grateful for every donation inspired by the project and deeply appreciative of all the rabbis who stepped up to help. Lives were saved and many thousands of people did not fall ill due to our efforts, and that’s something I’m very proud of.

Everything I write here is shared out of respect for the trust and support I’ve received.

“Everyone involved will be proud of the achievement.”

When I started the initiative, I believed that preventing a massive amount of death and suffering in children is something rabbis and Jewish communities would take great pride in.

I was certain that once we started doing a lot of good and our impressive early achievements are made known, the Reform movement and its leaders would see what an incredible opportunity this is to give the world an inspiring example of genuine Tikkun Olam with a kind of real-world impact that anyone could immediately understand.

By the spring of 2023, we indeed had these impressive early results, including, back then, enough money raised to protect around 20,000 people from malaria and save around 25 lives (raised almost entirely through one-on-one Zoom presentations, with no real budget to speak of).

At this stage I started introducing these results to plenty of people at Jewish organizations, many of whom were in positions of power and could have very easily amplified the results, saved far more lives, alleviated an incredible amount of human suffering in the name of 21st century Judaism, and received a lot of credit for helping some of the world’s most disenfranchised people.

Unfortunately, despite a lot of kind words about my efforts and my presentations, no one was interested in doing that.

In many of the conversations I had around this period, I was told that the beneficiaries of our effort are not Jewish, that it has nothing to do with supporting Israel, that there are other causes that are more pressing at the moment, and that this is just “not the type of thing our organisation does”. I often found myself asked to explain why saving children from malaria should interest a Jewish foundation/organization/federation (“What does all this have to do with the World Union?” was another thing I was asked many, many times throughout the project).

I had answers ready for such occasions, answers that stressed how being associated with preventing a massive amount of death and suffering would be great for any organisation, that it could help make them truly relevant, that it could inspire and engage young people of exactly the right kind, that this is a project with enormous real-world impact that could make everyone involved look good.

I didn’t particularly enjoy making these instrumental what’s-in-it-for-you-guys points, but I understood that it’s part of the job and I made sure I was always super polite and respectful and positive (perhaps to a fault).

What does preventing death and suffering have to do with 21st century Judaism and the Reform movement?

To be honest, the people asking these questions had a point.

Preventing the actual death and suffering of children indeed isn’t something we think much about and prioritize in the Jewish community. (To be fair, it’s not exactly a leading priority for other religious groups and movements either).

When faced with a choice between a purely performative gesture related to Israel or “Jewish leadership” and one that would effectively alleviate a lot of real-world suffering, the choice is always clear.

Even when it comes to Jewish initiatives in the developing world, if you look closely and honestly, the reality is that most of them are far more concerned with feel-good PR for the tribe (with giving the impression that Israel or the Jewish people are doing good around the world) than with actually preventing children from suffering and dying.

None of this is probably surprising or new to anyone reading this. It’s something I knew when I started the initiative, and you can say it's exactly the reason I felt it was so needed.

What did surprise me, though, was how even after so many people were helped in our first year of fundraising—lives saved, tens of thousands of people protected, thousands of cases of illness prevented—so few seemed to see the value of what we built together.

Even among the congregations involved—whose participation I’m still very grateful for—I can’t say that supporting life-saving charities has become a real priority. Most of the money raised was very quietly contributed by rabbis’ discretionary funds and/or synagogue committees, and, with a few heart-warming exceptions, I can’t say that most congregations have done much more than that so far.

The plan was for our initial achievement—getting over 30 congregations to directly support effective life-saving work—to be a starting point for something much bigger.

Unfortunately, I never had the chance or the funding to actually take the next step, actively visit the synagogues involved myself, and inspire donors, communities, and families to do substantially more (and this is painful to think of, as I’m certain there are so many people in these communities who would have loved to save lives with the project).

For many reasons—both within and beyond my control—I did not succeed in securing additional funding for the initiative itself, and I decided to continue running the initiative voluntarily without pay and without a budget. Several more lives have been saved since, but it’s been an uphill battle.

Recalibrating

It took me a while to come to terms with how this initiative is going to be a much more modest affair than I’d expected. Save a miracle, effective giving to life-saving charities is not going to take over the Reform movement by storm and show its deep commitment to universal values, Tikun Olam, and the sanctity of all human life.

There’s only so much you can do through Zoom calls, working alone without a budget from Warsaw, Poland, while the world is burning and everyone is busy, distracted, and distraught.

Accepting this was tough. Seeing firsthand how little bandwidth people (even good ones) have for the prevention of human suffering left me despondent for a while, and I still have moments in which I’m haunted by the sense that, knowing what I know, I should be doing a lot more, fighting much harder, being a lot more vocal.

Seeing the horrible civilian suffering in Gaza—which fills me with profound sadness and anger and shame as an Israeli citizen—gives me a similar feeling of frustration at all the people out there whose suffering is not taken seriously by the world and by the Jewish community.

For me, taking human suffering seriously is what this is all about, and in the past couple of years I’ve been struggling with the sense that not helping as many people as I feel I need to help means that I’ve personally fallen short.

Perhaps I have. But gradually acknowledging my limitations has been helpful.

An important thing I’ve realized is that my disappointment and frustration at not being able to do more shouldn’t prevent the project from helping the many more people it still can help (and it can still help a lot of people).

My new mindset: “Yes, it’s a small initiative. Now, how much more death suffering can it prevent?”

Despite my disappointment at the lacklustre level of engagement and at how this effort was received, the initiative has raised enough money in the past three years to protect tens of thousands of people from illness, prevent several thousands of them from falling ill, and save around 30 lives. Small and budget-less as it is, very few projects in the Jewish world have helped so many people in such a meaningful way.

In these depressing, devastating times, that’s not something to take for granted.

If and when the Reform movement and the Jewish world start treating real human suffering with the seriousness it deserves, I believe that efforts like this will come to mean a lot to the Jewish community (especially to young Jews, especially in the aftermath of the things done in our name in Gaza).

Until then, I will do my best to try and get synagogues to protect more people from malaria, get more children vaccinated, fund more Vitamin A supplements, and save more lives.

Let’s End on a Positive Note

With all my self doubt and soul-searching, it’s important for me to convey that there is still a lot to celebrate here.

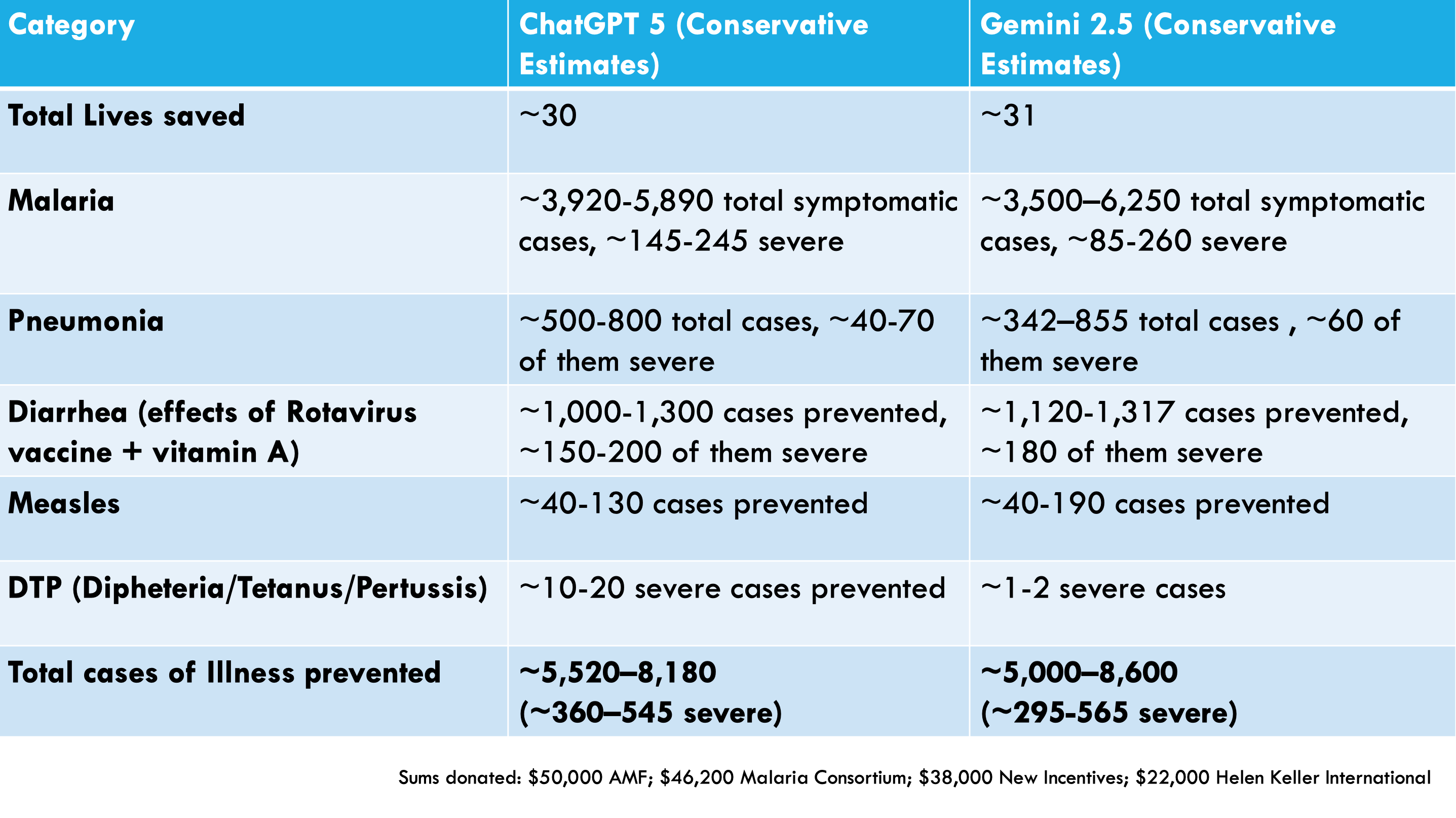

In an attempt to put the initiative’s impact on actual human lives into perspective (for myself and others), I recently asked both ChatGPT5 and Gemini 2.5 to separately break down the expected impact of the money our project has raised in terms of what kind of illnesses were prevented and approximately how many cases of each.

I asked both models to come up with their own conservative projections, diving deep into the sums we raised for each of the four charities, with GiveWell’s careful independent estimates as a starting point. I did several rounds of this, running every result and the assumptions behind it by other models.

Now, there are a whole lot of caveats and uncertainties here, and it’s important to keep in mind that these are just very general ballpark approximations, made for illustrative purposes only. But I do believe they give us a rough idea of the type and magnitude of illnesses that our project has managed to prevent. (If you want to know more about the process and about the assumptions and data used, I'll be happy to share everything!)

With all that in mind, you can see the numbers below. I think they show that everyone involved should, indeed, be proud of the project and that we have every reason to continue.