Recently, several rabbis—from both participating congregations and new ones—have told me they would love to introduce our initiative and its message to their congregations during the High Holy Days.

I’m a bit biased, of course, but I tend to agree that the initiative and what it stands for can be a powerful theme for the pulpit and quite a source for great High-Holy-Days sermon ideas.

Obviously, I am not a rabbi myself and I'm well-aware that each of the dozens of rabbis involved in the project have their own distinct voices, attitudes, interests and personalities. While I wouldn’t assume I can write a one-size fits all ‘Effective Giving Sermon,’ I do feel comfortable suggesting some ideas that could inform rabbis who would like to make effective giving a part of their holiday (especially Yom Kippur) sermons and lessons.

So here are some ideas that I believe could be at the center of a great effective giving sermon:

Unlike our ancestors, most Reform Jews today are in a position to prevent an immense amount of dangerous illness and human suffering every year. How does this affect our sense of responsibility, imperative, and moral deliberation on Yom Kippur?

The world in which the people of of Israel were commanded to set aside a special day for atonement and moral reflection was, of course, a very different world than the one we live in today. The poor Hebrew-speaking nomads wandering in the Sinai desert could not possibly be expected to see beyond their own community, beyond their own tribe, and beyond the vast desert sands surrounding them in every direction.

To understand just how different their world was from ours, just consider Korah, who according to Talmudic sources was a man of vast wealth (in fact, to this day, the Hebrew idiom for “filthy rich” is עשיר כקורח, which translates to “as rich as Korah”).

Korah, who later famously led a rebellion against Moses, was essentially the richest Israelite coming out of Egypt. Yet even Korah did not have the power to protect thousands of people every year from a deadly disease with just a negligible part of his enormous wealth. The average American Jew today can, and with no more than the click of a button.

Today we live in a world in which, according to very reliable data, it costs no more than $5 to protect two people from malaria for about two years. For a few thousand dollars one can prevent several hundreds of cases of this dangerous illness and save the life of a child. What this means is that the average Jewish person is, from the perspective of the world’s poorest billion people, in a position of immense power. They can regularly prevent a great deal of human suffering, dramatic health scares, unthinkable sorrow.

Many of us have very strong beliefs about the responsibilities of our leaders and of people, like Korah, in positions of power (and we most certainly should!). But how many of us truly consider the profound sense in which we ourselves are the powerful, in which we ourselves are more than capable of directly helping a vast number of suffering people with their suffering (and that no one else will help these particular people if we don’t).

This is obviously not a problem that the ancient Israelites—or most Jews throughout history—ever had to deal with. The command to atone was given to much poorer people than us, living in a much smaller, simpler world. The only suffering and wrongdoing they were expected to care about was right there in front of them. We might be tempted to pretend that we are in a similar situation as our ancestors were and that nothing more is required of us, but that would be too easy (and Yom Kippur is not about being easy!).

Does the fact that most of us could save a life this year without much difficulty change how we treat our moral responsibilities? Does it change what is required from us, what we require from ourselves as Jews and as human beings?

What are moral reflection and atonement without (effective) action?

Our Jewish tradition is a tradition of action. In contrast to christianity (or at least many forms of christianity), where adherents are expected to hold certain beliefs, the Jewish tradition is one that emphasizes doing. A Hebrew phrase often used to describe a devout Jew is Yehudi Shomer Mitzvot—a Jew who fulfils the mitzvot, the commandments. In that sense, the idea of Orthodox Judaism is somewhat of a misnomer. Orthodoxy is the idea of having the “correct belief,” while orthopraxy is the idea of having the “correct conduct.” Being a devout Jew demands orthopraxy, not orthodoxy.

This is an interesting thing to consider on Yom Kippur, which one might think is all about about our personal reflection and the inner workings of our souls.

But if we consider what is demanded of us a bit more carefully, the call for action, for doing, is quite clear.

Besides the fact that coming together to proclaim that “Ashamnu, Bagadnu, Galaznu…” is in itself very public performative act, it seems that the very idea of an atonement that is not followed by any change in one’s conduct—or that doesn’t at least aspire to such change—is, to say the least, problematic. The “Al Chet” is not a text we recite for aesthetic enjoyment, but a solemn clarion call to acknowledge our faults, ask for forgiveness, and try to do better.

The same can be said for our moral deliberation all year round. The Jewish ethical tradition is not there for our own personal enjoyment or for our own highbrow cultural consumption. It is not meant to just move us, but to move us toward meaningful action, on a personal, communal, and human level.

The iconic Yom Kippur prayers—or a beautiful Heschel quote about our responsibility to resist evil, for that matter—are not there to make us feel proud and pleased with how noble our predecessors’ ideals were and how eloquently they were expressed. They are meant to make us think: are we really making an honest, serious effort to help others? Whose cries are we ignoring? Who are we in a position to truly help, and what are we doing to effectively help them?

There are many levels on which one could think about these questions, of course—one person might focus on family and friends, another might think of racial justice; one could think of them as a Jew, as an American, as a parent, as a son or daughter, or as a human being.

One thing to keep in mind—especially for those of us who don’t know where to start—is that we are in position to help others in a profound way in this coming year. A great example of this, to me, is that the average Reform Jew could, without much difficulty, directly prevent hundreds of people from falling ill, protect children from horrific illnesses such as measles and tuberculosis, help parents avoid nasty health scares and the ultimate sorrow of losing their child. The four life-saving charities we support represent four ways in which we can, with a great deal of confidence, ensure that we are doing something to meaningfully help people in need.

In a world in which around 15,000 children and 800 women die every day mostly of preventable preventable causes—and in which there are some incredibly inspiring efforts to help them, one thing that we cannot say is that we that are not in a position to do a lot of good. There are real people out there whom only we can help and lives that only we can save.

There is a wonderful Elie Weisel quote that I’ve recently added to my introductory presentation about effective giving: “A Jew must be sensitive to the pain of all human beings. A Jew cannot remain indifferent to human suffering, whether in other countries or in our own cities and towns. The mission of the Jewish people has never been to make the world more Jewish, but to make it more human.”

A commitment to alleviating at least a little bit of human suffering—and making the world more liveable for at least some people out there—is one great way to make our ethical deliberations this year truly count.

A reading of the Book of Jonah: On tribal myopia, our responsibilities to the world, and our sense of proportion

David Ben-Gurion once wrote that “there is a whole book in the bible, Jonah, dedicated to the idea that God’s mercy is given equally to all the nations, to the pagans as well as to the people of Israel” (Netzach Israel, 1964, my translation).

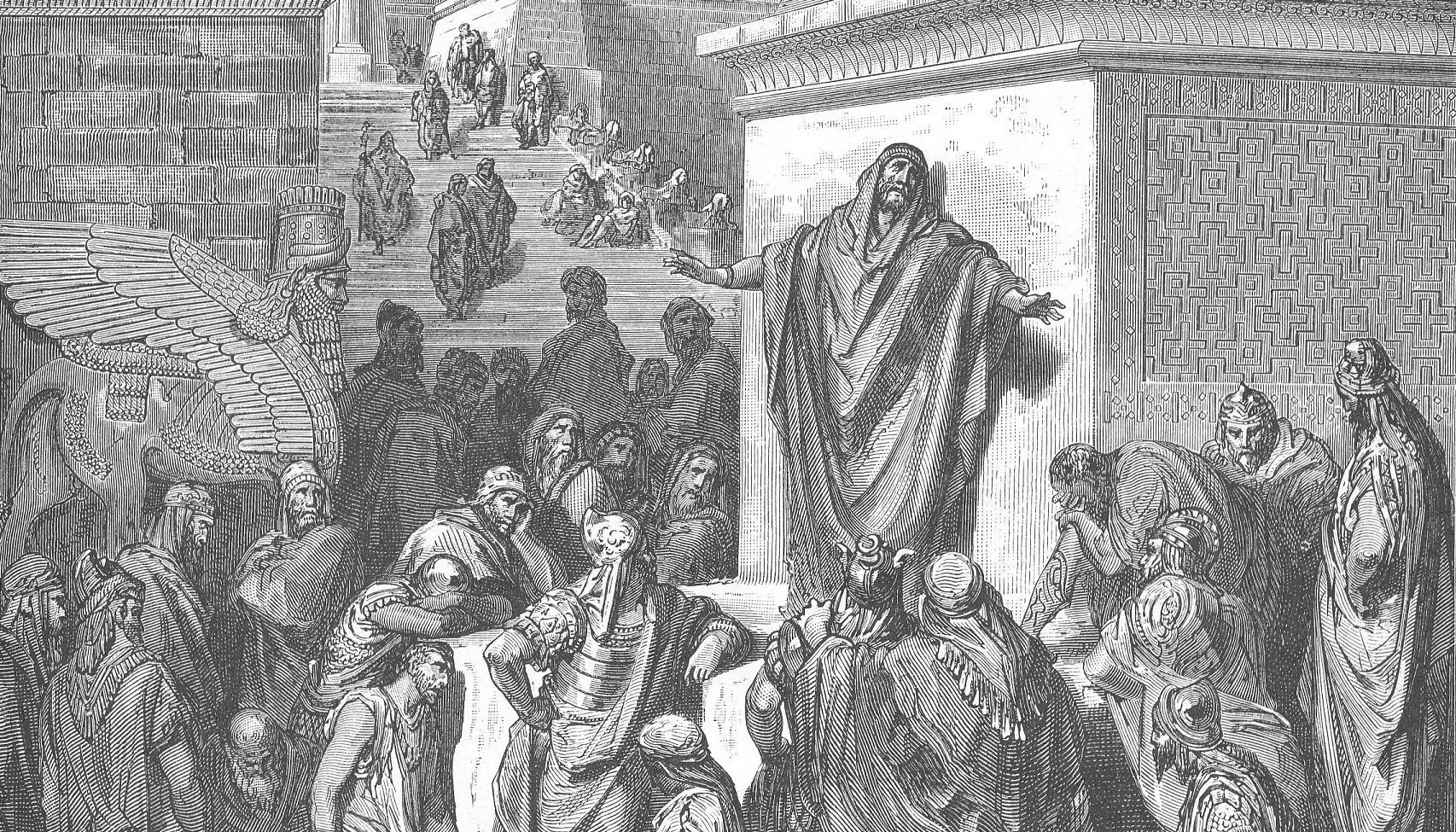

I believe that this explosive little book—read at the middle of the most solemn day of the Jewish calendar—goes even further than that and still has a whole lot to teach us about how tribal myopia can blind us to the most basic compassion and to our most obvious responsibilities to others.

When Jonah introduces himself to the terrified sailors during the storm, he says “I am a Hebrew and I worship the Lord, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land.” Yet his reluctance to help the people of Nineveh is so intense that he not only disobeys God’s direct orders and tries to flee him (almost comically, on a ship!), but actually expresses anger after they repent and the Lord spares them from destruction. (And this is, mind you, after his atonement!)

There are different explanations for Jonah’s extreme reluctance to help the people of Nineveh. One possible explanation is that he saw these Assyrians as enemies of Israel and he did not want to help them harm his own people. Another is that he ideologically believed that such idolaters should not be shown forgiveness and be given the opportunity to repent and to be spared. In any case, he is very explicitly displeased with the success of his mission, and unequivocally shows a deep disregard for the lives and well-being of the many human beings he was ordered to save (for which he is quite clearly rebuked by God).

Why did God choose this particular character to help these non-Jewish idolaters in a faraway land? Why not let Jonah focus on his own community and his own people, and leave the reformation of Nineveh to someone who at least has a minimal appreciation for the value of human life and divine mercy?

While you could argue that there’s no need to ask such questions—Jonah was sent to where he was needed most and where there were a tremendous amount of people to be helped—I believe there is a lesson here that only someone like Jonah could teach us:

If our tribal allegiance is so strong that we do not care about the life and death of human beings that we know we can and should help, whoever and wherever they are, this is at odds with everything that is holy and just. The book uses Jonah to teach us about the inherent value of all human life and to make a strong statement about how our moral responsibility as Jews extends to all of God’s children.

The extent of Jonah’s blindness about this is beautifully illustrated at the end of the book, with the contrast between his outrage about God ruining the plant that provided him with shade and his lack of concern for the fate of 120,000 human beings. I believe that the enormous number of people is not mentioned by accident—it is there to suggest that even the opportunity to do an extraordinary amount of good can often be dismissed by someone who is only concerned with himself, his own lot, and his own people.

The sheer scale of death and suffering Jonah was able to prevent—and his utter inability to appreciate it—should make us all think long and hard. Would we also value a plant that gave us a few hours of shade more than the well-being of over one hundred and twenty thousand human beings? How much suffering prevented, how many lives saved, are enough to make us care?

This last question has had a constant presence in my life in the past few years, as my main mission has been to explain to as many rabbis, Jewish leaders, and Jewish donors as I can that they can all—without the burden of going to Nineveh—save quite a lot of lives and prevent quite a lot of actual human suffering (of innocent people who aren’t involved in any “wickedness”). I am still amazed that a few thousand dollars donated to the Against Malaria Foundation can actually—based on reliable, independent sources—prevent hundreds of people from falling ill (including many severe cases) and save a life. To me, knowing that you can so easily prevent so much illness and suffering is such an exciting opportunity that it has to be seized with two hands.

And yet I am keenly aware that most people don’t see it that way. In fact, I would go even further and say that Jonah’s lack of concern for the fate of 120,000 of God’s own children does not surprise me at all. Appreciating the scale and urgency of the needs of others is quite difficult for most of us, especially when the others we can help are far away.

In the past year, our initiative has raised enough to provide about 20,000 human beings with protection from malaria (either nets of a full course of antimalarial medicine), and yet and I can very easily sense that this number seems like an abstraction to most of the people who encounter it. Providing 20,000 people with protection from a dangerous illness for two years, providing 2,000 people with one meal they might have received elsewhere, providing 200 people with a symbolic gesture that they hardly notice—it all very often sounds the same to us, and so few of us take a moment to consider the details (which are just about everything from the perspective of the people helped).

Like Jonah, we still so rarely appreciate the scale of human suffering that we are in a position to prevent. If you need any evidence of this, just consider how utterly non-existent the developing world (which is, without a doubt, where a little bit more of our resources and attention can prevent the most actual suffering) is in our moral and political deliberations. Even among liberal-minded, well-meaning, and/or progressive people in the 21st century, the most amazing opportunities to alleviate the suffering of others are not merely rejected — they aren't even given any meaningful consideration. I would say that the problem is that we are more concerned with our own leafy plants and the shade they provide us with, but that would be an understatement: Jonah at least genuinely needed that plant to avoid the blistering heat; we have plenty of shade above our heads…

The book of Jonah ends well, though. Jonah eventually saved the lives he needed to save. It definitely helped that he was the protagonist of a biblical legend, where God himself directly told him what his responsibilities are and didn’t let him off the hook until they were fulfilled. It’s a consoling (though bittersweet) thought that while Jonah didn’t care about the fate of the people he helped, the people themselves cared, and so did God.

Our responsibilities are much less clearly defined, of course, and we are quite skilful at rationalizing them away. Like with Jonah, the people we can help the most are very often beyond our borders and off our moral radars; we don’t see their suffering, and we thus don’t understand why we should care. For as long as that remains the case, the lesson of Jonah will remain incredibly needed.

We can also keep things light and simple: Committing to save a life is a beautiful, joyous way of celebrating the new year.

I admit that this post—and my suggestions thus far—have been quite heavy. Our effort to prevent death and suffering in the developing world definitely sounds like a more obvious fit for Yom Kippur than for Rosh Hashanah, and I suppose that I intuitively picked up on this.

But it needn’t be so. As in the case of the life-saving bar mitzvah, I believe that there is plenty of potential here to positively, joyously add meaning and beauty to an ancient Jewish ritual.

Rosh Hashanah—the ultimate holiday of new beginnings—is a wonderful opportunity to tell your congregation that this year you will try to save a life together and prevent a whole lot of disease and suffering with one (or more) of the world’s most well-vetted life-saving charities.

If your synagogue is one of the over 30 congregations that have already fulfilled their Life-saving Congregation pledges, you can also use the opportunity to proudly say that in the outgoing year (5783) your congregation played an important part in a new and growing effort that has already, in its first year, provided ~20,000 people with protection from malaria (either nets or antimalarial medicine), fully vaccinated ~200 infants, and saved ~25 lives.

The same life-affirming attitude could actually be extended to Yom Kippur. Communally saving a life together—helping another human being whose name you will never know have a Chatima Tova—can be a beautiful affair and something to celebrate and inspire others with.

People often associate both Yom Kippur and helping people in the developing world with sadness and somberness. No sadness or somberness are necessary, though—what is necessary is that we do more good in the world, be kinder to each other, and help the people we know we need to help.

(A very early) Shana Tova and Chatima Tova to everyone!